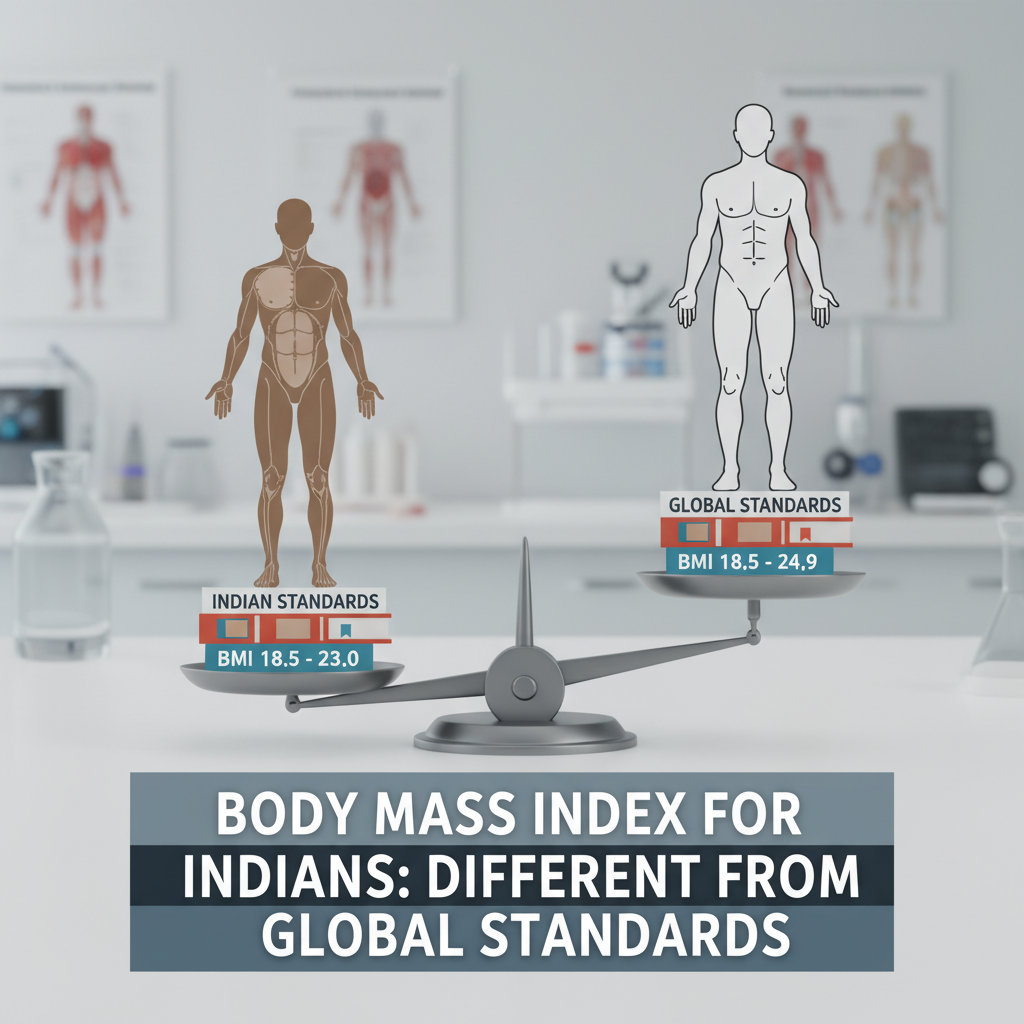

The Global Standard vs. Indian Reality: Why BMI for Indians Different Global Standards is Essential

For decades, the Body Mass Index (BMI) has served as the primary tool globally for screening weight categories. Calculated simply by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m²), the World Health Organization (WHO) established clear cutoffs: a BMI of 25.0 kg/m² or higher signals overweight, and 30.0 kg/m² or higher indicates obesity.

However, this universal yardstick often fails when applied to specific ethnic groups, particularly those of South Asian descent. The fundamental truth is that the bmi for indians different global standards is a necessity, not just a preference. Research consistently shows that Indians are susceptible to metabolic diseases, such as Type 2 Diabetes and cardiovascular risks, at much lower BMI levels than their Caucasian counterparts. This critical difference requires a re-evaluation of what constitutes a ‘healthy’ weight range for the Indian population.

If you are looking to assess your current status using the specialized thresholds, you can use an accurate Indian BMI Calculator.

The Core Problem: Why Standard BMI Thresholds Don’t Work for Indians

The discrepancy arises from fundamental differences in body composition. While BMI measures total body mass relative to height, it does not distinguish between fat mass and lean muscle mass. This is where the concept of the “thin-fat Indian” comes into play.

Ethnic Differences in Body Composition

Indians, on average, tend to have a higher percentage of body fat for any given BMI compared to Caucasians. Furthermore, this fat is often distributed centrally, accumulating around the abdominal organs (visceral fat). Visceral fat is metabolically active and highly inflammatory, making it a major driver of insulin resistance and chronic diseases.

A person of Indian origin might have a seemingly ‘normal’ BMI of 23 kg/m² but possess the body fat percentage and metabolic risk profile of a Western individual with a BMI of 27 kg/m². Ignoring this physiological reality means many Indians fall into the ‘normal weight’ category on global charts while silently harboring significant health risks.

WHO Standard BMI Cutoffs (Global)

- Normal Weight: 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m²

- Overweight: 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m²

- Obesity (Class I): 30.0 kg/m² and above

These standards are primarily derived from European populations.

Specialized BMI Cutoffs (Indian/Asian)

- Normal Weight: 18.5 – 22.9 kg/m²

- Overweight: 23.0 – 24.9 kg/m²

- Obesity (Class I): 25.0 kg/m² and above

These lower thresholds acknowledge higher fat mass and metabolic risk at lower BMI.

Defining the New Cutoffs: What Makes BMI for Indians Different Global Standards?

Recognizing the urgent need for population-specific guidelines, several major health bodies and consensus groups in Asia have proposed and adopted lower BMI thresholds. These recommendations aim to capture the risk earlier, allowing for timely intervention and lifestyle modifications.

The Rationale Behind Lower Thresholds

The revised guidelines were developed based on epidemiological studies linking specific BMI ranges to increased prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia within South Asian populations. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the Consensus Group for Asian Indians have been instrumental in advocating for these changes.

The key takeaway is that for an Indian adult, the danger zone begins much sooner. A BMI of 23 kg/m², which is considered well within the normal range by global standards, is classified as ‘overweight’ for an Indian individual. When we discuss bmi for indians different global standards, we are talking about saving lives by adjusting the definition of risk.

According to research published by institutions focusing on metabolic health in South Asia, the risk of developing Type 2 Diabetes mellitus increases exponentially once the BMI crosses 23 kg/m² in Indian populations. This is a crucial piece of data that underscores the necessity of using specialized metrics.

Health Implications of Using the Wrong BMI Standards

The failure to use appropriate BMI cutoffs has significant public health consequences. If an Indian patient is told they are ‘normal weight’ based on a global BMI of 24.5, they may delay necessary lifestyle changes, oblivious to the fact that they are already at high risk for metabolic syndrome.

Understanding Visceral Fat and Metabolic Risk

The problem is not just being overweight; it is where the fat is stored. Visceral adiposity (fat around internal organs) is strongly linked to insulin resistance, regardless of subcutaneous fat (fat under the skin). Indians have a genetic predisposition to store fat viscerally.

Impact of Misclassification:

- Delayed Intervention: Patients receive late or no warning about impending metabolic issues.

- Increased Disease Burden: Higher rates of undetected hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the ‘normal weight’ category.

- Public Health Planning Errors: Underestimation of the true prevalence of obesity-related risks in the population, leading to inadequate resource allocation for prevention programs.

Dr. V. Mohan, a leading diabetologist in India, often states, "For Indians, the definition of healthy weight is slimmer. We must treat a BMI of 25 as obesity, not merely overweight, because the metabolic consequences are already severe at that point."

Practical Application: Calculating and Interpreting BMI for Indians Different Global Standards

While BMI remains a valuable screening tool, its interpretation must be contextualized. For Indian adults, the focus should shift to the lower thresholds. However, it is also crucial to move beyond BMI alone and incorporate other, more accurate measures of central obesity.

Step 1: Calculate Your BMI

Use the standard formula (kg/m²) or an online calculator. Record the number accurately.

Step 2: Apply Indian Thresholds

Compare your result against the revised Indian cutoffs (23.0 = Overweight; 25.0 = Obese). This redefines your risk category.

Step 3: Measure Waist Circumference (WC)

This is the most critical supplementary measurement. For Indian men, WC > 90 cm is high risk. For Indian women, WC > 80 cm is high risk.

Beyond BMI: Comprehensive Health Assessment

For a truly accurate picture of metabolic health, BMI and Waist Circumference should be combined with blood tests. These include fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid profiles. Furthermore, understanding the balance of protein, fats, and carbohydrates is vital for managing visceral fat, which can be aided by specialized tools like a metabolic health assessment tool.

It is important to remember that fitness trumps fatness to some extent. A highly muscular individual with a BMI of 26 might be metabolically healthier than a sedentary individual with a BMI of 22 who carries high visceral fat. However, given the genetic predisposition of Indians toward visceral adiposity, relying solely on visual appearance is risky.

The Asian Pacific Perspective on the classification of weight status provides detailed scientific backing for these adjusted cutoffs, emphasizing that population-specific anthropometric studies are non-negotiable for effective disease prevention. The WHO itself acknowledges the need for lower cutoffs for Asian populations, though the primary global standard remains high.

Implementing Lifestyle Changes Based on Indian BMI Standards

If your BMI falls into the high-risk category (23.0 kg/m² or above) according to the Indian standards, immediate lifestyle modifications are warranted. These changes focus less on drastic weight loss and more on improving body composition and reducing visceral fat.

Dietary Focus: Low Glycemic Index

Prioritize whole grains, pulses, and high-fiber vegetables. Reduce refined carbohydrates (maida, white rice, sugar) which contribute directly to insulin resistance and visceral fat storage.

Exercise Focus: Resistance Training

While cardio burns calories, resistance training (weight lifting, bodyweight exercises) builds muscle mass. Increased muscle mass improves glucose uptake and metabolic efficiency, counteracting the ‘thin-fat’ phenotype.

Stress and Sleep Management

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which promotes central fat deposition. Adequate sleep and stress reduction techniques (like yoga or meditation) are crucial components of metabolic health management.

The shift in perspective—from chasing a global BMI goal to achieving a metabolically healthy body composition—is key for the Indian population. By adhering to the lower thresholds, healthcare professionals and individuals can proactively address the rising tide of non-communicable diseases in the country.

Conclusion: Embracing the Specificity of BMI for Indians Different Global Standards

The evidence is overwhelming: the standard global BMI thresholds do not serve the Indian population accurately. Due to unique body composition, higher body fat percentage at lower weights, and a genetic predisposition towards visceral fat storage, the risk of metabolic disease begins significantly earlier. Recognizing that bmi for indians different global standards is a critical public health measure allows for earlier diagnosis, preventative intervention, and ultimately, better health outcomes.

By adopting cutoffs where Overweight starts at 23.0 kg/m² and Obesity starts at 25.0 kg/m², coupled with essential measurements like Waist Circumference, Indians can navigate their health journey with far greater precision and safety. This specialized approach ensures that the screening tool matches the physiological reality of the population it serves.

For further authoritative reading on the scientific basis for these lower cutoffs, the consensus statement published in major journals provides comprehensive data on the need for ethnic-specific guidelines. The Lancet has published findings detailing the association between BMI and mortality in Asian populations, supporting the lower thresholds.

FAQs

The specialized cutoffs recommended for Indians are: Normal weight (18.5–22.9 kg/m²), Overweight (23.0–24.9 kg/m²), and Obese (25.0 kg/m² and above). These are significantly lower than the global WHO standards.

This is due to the "thin-fat" phenotype. Indians generally have a higher percentage of body fat and a greater tendency for central or visceral fat deposition (fat stored around internal organs) even when their overall BMI is low. Visceral fat is highly linked to insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

No. While BMI is a good screening tool, it should always be supplemented by measuring Waist Circumference (WC). A WC greater than 90 cm for men and 80 cm for women of Indian ethnicity indicates high central adiposity and significantly elevated metabolic risk, even if the BMI is in the normal range.

These recommendations are based on consensus guidelines developed by various medical and research bodies, including the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and specialized Asian consensus groups, following large-scale epidemiological studies specific to South Asian populations.

A BMI of 24.0 kg/m² falls into the ‘Overweight’ category according to the specialized Indian standards (23.0–24.9 kg/m²). This places you in a high-risk group where proactive lifestyle changes are strongly recommended to prevent the onset of metabolic syndrome.